Black History Month: five Black Britons they don’t teach you about in school

Black history is British history. Black contributions to Britain can be traced back to the Roman period, when North African soldiers established Britain’s first known African community.

Black History Month, established in October 1987 under the leadership of Akyaaba Addai-Sebo, is a significant and specific moment for recognising the contributions Black Britons have made to the country.

However, when celebrating this BHM it is important to acknowledge that its existence forms part of erasing the legacy of British colonialism that seeks to erase the contributions of black Britons.

Increasingly there have been student-led discussions and protests about diversifying the British school curriculum to include BIPOC (British, Indigenous and People of Colour) history. With that in mind, and in the spirit of BHM, here are five famous Black Brits who you might not have learnt about at school.

Olive Morris (26th June 1952-12th July 1979)

A mural of Morris. Image credit: Breeze Yoko

In her short life, Olive Morris, a Jamaican-born Windrush generation activist, was at the centre of organising the Black Women’s Movement in Britain. Morris drew attention to the intersections of race, class and gender during the Second Wave of feminism, which failed to be inclusive. Morris co-founded the Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent and aided in establishing the Brixton Black Women’s Group. She was also involved in the British Black Panther Movement, emphasising the experiences of ordinary black Britons, in particular fighting for adequate housing.

Morris has been honoured and remembered by the Lambeth Council with the Olive Morris Memorial Collection in the Lambeth archives and the naming of a building in her honour in her native Brixton. She left a trailblazing legacy of activism in Brixton and the wider UK that remains relevant today.

2. Jack Leslie (17th August 1901-25th November 1988)

Jack Leslie is one of Britain’s greatest black football players. Spending almost his entire career playing for Plymouth Argyle (1921-35), Leslie was the only black professional player in England at the time. With over 400 appearances and scoring more than 100 goals for the Argyle team, Leslie’s story remains relatively buried in the wider history of English football.

“As one of Britain’s most important black footballers, Leslie is beginning to gain the national recognition he deserves“

Despite his talent and popularity amongst Plymouth supporters and opposing teams, Leslie’s career was not untouched by racism. Having been selected to play for England in 1925, Leslie would have become the first black person to play for the nation. However, the invitation was withdrawn from the team soon after it was discovered he was black. He was never chosen again. It was not until 1978, when Viv Anderson was picked, that a black player played for England.

Recently, a community crowdfunding campaign has raised over £100,000 to raise a statue of Leslie outside Plymouth Argyle’s Home Park. As one of Britain’s most important black footballers, Leslie is beginning to gain the national recognition he sorely deserves as a pioneer for racial equality in sports.

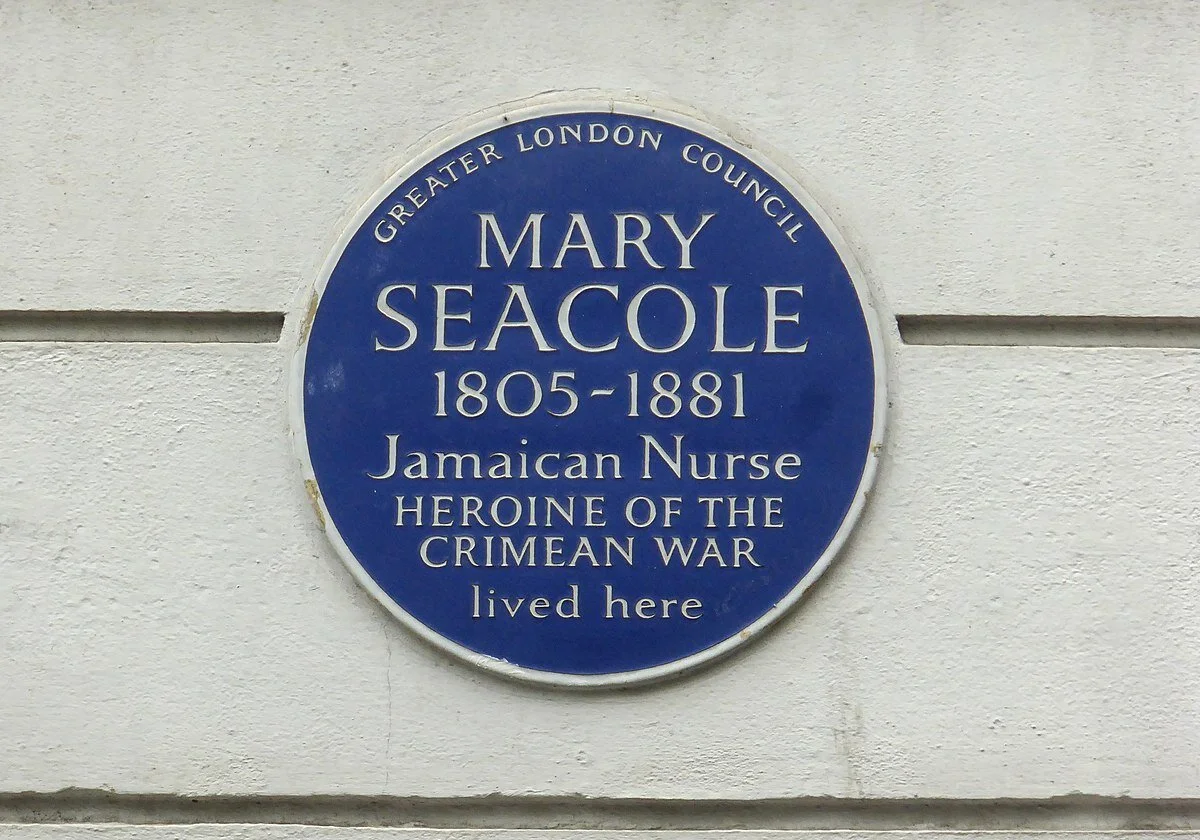

3. Mary Seacole (23rd November 1805-14th May 1881)

Heard of Florence Nightingale? Well, British-Jamaican nurse Mary Seacole was an incredible, and overlooked, contemporary of hers during the Crimean War (1853-56). Born in Jamaica, to a Jamaican mother and Scottish father, Seacole had very few civil rights.

Having been taught nursing and healing (traditional Jamaican obeah) by her mother, in 1854, Seacole travelled to England to approach the War Office to be taken on as an army nurse in the Crimea. However, she was refused.

Undaunted, she funded her own trip to Crimea, where she established the British Hotel near Balaclava with Thomas Day as well as visiting the battlefield, often under fire, in order to nurse the wounded. She was known as fondly as ‘Mother Seacole’ and her reputation rivalled Nightgale’s.

Image credit: Ethan Doyle White

Returning to Britain at the end of the war, soldiers wrote letters to newspapers praising her bravery and kindness on the frontlines of the war. In 1857, after a fund-raising gala to support her, Seacole published her popular autobiography, ‘The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs Seacole’.

Despite her popularity and the significance of her reputation in Britain, after her death for almost 100 years, Seacole was lost to history. It was not until 1973, when her grave was rediscovered and restored by the British Commonwealth Nurses’ Memorial Fund and the Lignum Vitae Club, that Seacole re-entered historical discourse.

Recognition of Seacole’s work has been most significant in the 21st century. In 2004, Seacole was voted the Greatest Black Briton and in 2016, a statue of her was unveiled in the grounds of St Thomas’ Hospital (London’s Southbank). Seacole evidences the importance of ensuring we recognise the often hidden black figures of British history.

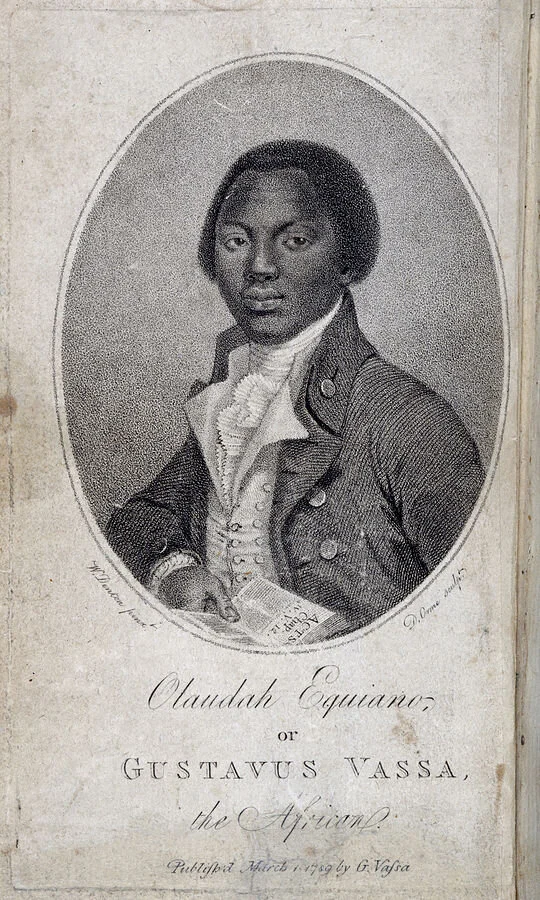

4. Olaudah Equiano (1745-31 March 1797)

Olaudah Equiano was born in the Eboe province, which is now in modern-day Nigeria. Whilst details about his early life are unknown, from 1786, Equiano became a leading abolitionist figure as a result of his experiences of enslavement in Virginia from childhood until he bought his own freedom in 1766.

Image credit: The British Library

Equiano was a prominent member of the ‘Sons of Africa’, a group of 12 black African men, living in Britain, who campaigned against the slave-trade and for the abolition of slavery. This group can be considered Britain’s first black political organisation and included other significant abolitionist figures such as Ottobah Cugoano.

Working alongside the ‘Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade’, Equiano led delegations of the ‘Sons of Africa’ to Parliament to persuade MPs to abolish the international slave trade in the British colonies (achieved in 1807).

Equiano leveraged his literacy alongside other ‘Sons’ in order to represent the interests of black people across the world. His autobiography, ‘The Interesting Narrative of the life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa, the African’ (1789) was a hugely popular work (running through nine English editions in his lifetime), aiding the abolitionist cause, as one of the earliest books published by a black African writer.

Equiano is considered the originator of the ‘slave narrative’ through his first-hand literary testimonies that evidenced the brutality of enslavement, but also demonstrated his pride in being African. As a pioneer, Equiano is Britain’s most famous Black abolitionist.

5. Harold Moody (8th October 1882-24th April 1947)

Jamaican-born Harold Moody was a doctor and activist who campaigned against racial prejudice and inequality. Migrating to Britain in order to study medicine at King’s College London (1904), Moody found himself unable to get a job due to racism - despite graduating top of his class in 1910.

Consequently, he established his own medical practise in Peckham, south-east London where he became a leading figure in the British civil rights movement and the global fight against racism. His activism crossed boundaries; devoted to his faith, as President of the London Christian Endeavour Federation Moody would advocate for those facing discrimination in the Peckham community.

“Moody has been referred to as the British Martin Luther King Jr. and he no doubt significantly advanced the fight for racial equality in Britain”

In March 1931 Moody established the League of Coloured Peoples, often considered the UK’s first civil rights group. Its executive members included major players such as Belfield Clark (Barbados), George Roberts (Trinidad), Samson Morris (Grenada), Robert Adams (British Guiana) and Desmond Buckle (Ghana). Other members who went on to become major figures included writer and activist Una Marson and future Kenyan President Jomo Kenyatta.

The group fought against discriminatory housing and employment policies and practises in Briton, aiming to improve race relations. The group were also credited with overturning the Special Restriction Order of 1925, lifting the colour bar in the British Armed Forces in 1942. Utilising its quarterly journal, The Keys, to promote its efforts, the group presented a “Charter of coloured peoples” which would form the basis of the resolutions made at the 5th Pan-African Congress in Manchester (1945).

As ambassador of the British black community, Moody has been referred to as the British Martin Luther King Jr. and he no doubt significantly advanced the fight for racial equality in Britain.